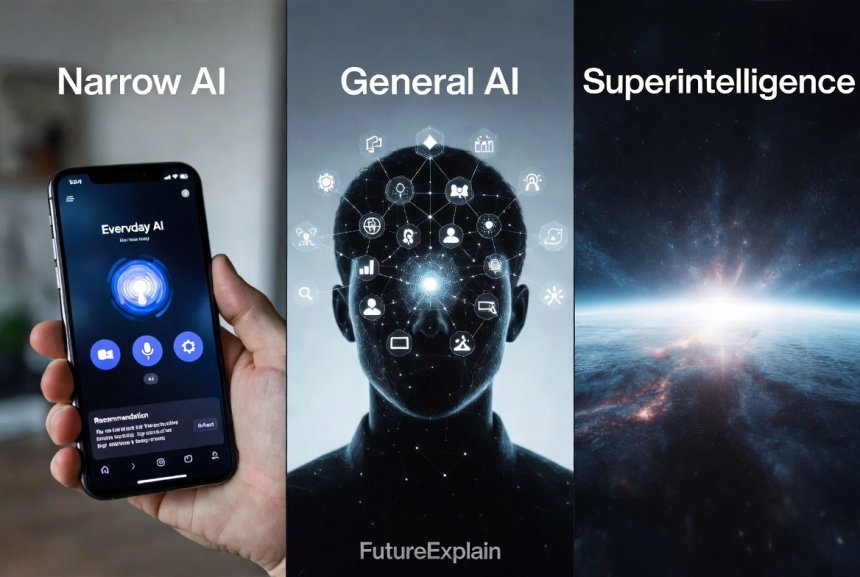

Types of Artificial Intelligence: Narrow vs General vs Super AI

This article explains the commonly used categories of artificial intelligence—Artificial Narrow Intelligence (ANI), Artificial General Intelligence (AGI), and Artificial Superintelligence (ASI)—in plain language. It separates current reality (mostly ANI) from research goals and speculation, gives concrete examples of narrow AI in use today, and explains what AGI and ASI mean, why timelines are uncertain, and which societal concerns are practical today versus hypothetical. The piece includes a short decision checklist for readers weighing news claims about AGI, notes on risk prioritization, and a brief primer on safety and governance. Tone is calm, non-hyped, and aimed at beginners, managers, and students who need to understand the distinctions without technical jargon.

Types of Artificial Intelligence: Narrow vs General vs Super AI — An Updated, In-Depth Guide

This article explains, in clear and careful language, the commonly used categories of artificial intelligence—Artificial Narrow Intelligence (ANI), Artificial General Intelligence (AGI), and Artificial Superintelligence (ASI). The purpose is practical clarity: to separate what exists today from research goals and speculative futures, to outline realistic near-term risks that matter for organizations and societies, and to give managers, students, and non-technical readers a usable checklist for interpreting news, evaluating vendor claims, and making responsible decisions.

Why precision matters when we talk about “AI”

The word “AI” is used in many ways. It can mean a simple rule-based automation, a statistical model trained to recognise patterns, or even an imagined future machine with human-level reasoning. That mixture creates confusion: it makes some technologies look more capable than they are, and it can distract attention from real problems that affect people today. Using precise categories—narrow, general, and superintelligence—helps separate immediate policy, engineering, and ethical choices from longer-term research debates.

Short, practical definitions

- Artificial Narrow Intelligence (ANI): Systems designed to perform a specific task or a narrow set of tasks. Examples: image classifiers, search ranking, voice command execution, and fraud detection. ANI systems are widely deployed and commercially valuable.

- Artificial General Intelligence (AGI): A theoretical system that can understand, learn, and apply intelligence across a wide range of tasks at least as well as a typical human. AGI remains a research objective rather than an established technology.

- Artificial Superintelligence (ASI): A hypothetical future system whose cognitive capabilities exceed those of humans across virtually all domains. ASI is speculative and depends on unresolved scientific and engineering breakthroughs.

How to read this article

Read the sections on ANI for practical, operational knowledge—these describe technologies you will encounter in products and services today. Read the AGI and ASI sections for research context and to understand long-term debates. Throughout the article you will find a number of pragmatic checklists and governance suggestions you can apply immediately.

Part 1 — Artificial Narrow Intelligence (ANI): Reality and practical implications

What ANI is, in plain language

ANI systems are built to do specific jobs. They learn patterns from data or follow explicitly programmed rules. The key point is scope: each system is specialised. A model that tags photos for faces cannot automatically answer medical questions; a language model that summarizes articles is not the same as a model that diagnoses diseases without further engineering and validation.

Common examples you already use

- Recommendation systems on e-commerce and streaming platforms that suggest products or media.

- Search engines that rank results and auto-complete queries.

- Spam filters, content moderation tools, and email categorization.

- Image recognition models used in photography apps and safety checks.

- Speech-to-text and text-to-speech components used in virtual assistants and accessibility tools.

Why ANI matters economically and socially

ANI systems create real economic value by increasing speed, reducing manual effort, and enabling scale. They power automation that transforms customer service, logistics, finance, and healthcare workflows. They also create social and governance challenges: biased training data can lead to unfair outcomes; brittle models can fail unexpectedly in novel conditions; and tools that are easy to misuse (deepfakes, scalable disinformation) raise societal harms.

Limitations and failure modes of ANI

Understanding common failure modes helps organisations deploy ANI responsibly:

- Distribution shift: A model trained on one population of data performs poorly when the input distribution changes.

- Edge cases: Rare or novel inputs can produce unpredictable outputs because the model has not seen similar examples in training.

- Bias amplification: Models trained on biased datasets may amplify existing inequities.

- Overfitting: Models may memorize training data patterns and fail to generalize to new examples.

- Lack of explainability: Some models, especially deep learning models, are hard to interpret; that complicates debugging and auditing.

Operational controls that reduce risk today

Practical steps organisations can take to manage ANI risks include:

- Maintain a data inventory and validate that training data reflect the target population.

- Use held-out test sets and realistic stress tests that simulate real operational conditions.

- Implement monitoring for performance drift and set alert thresholds.

- Provide human-in-the-loop review for high-risk cases and transparent feedback channels.

- Document limitations, known failure modes, and appropriate use cases in a simple “model card” for each deployment.

Part 2 — Artificial General Intelligence (AGI): What it means and why it is debated

Defining AGI carefully

AGI refers to an intelligence that can perform a broad set of cognitive tasks at levels comparable to humans. Key expected properties include the ability to learn new tasks with limited examples, to transfer skills across domains, to reason, plan, and to exhibit flexible problem solving. Importantly, AGI is defined by capability, not by a single algorithm or architecture.

Why AGI is still an open research question

Despite dramatic progress in many AI benchmarks and the emergence of increasingly capable models, AGI remains unresolved because the qualities that constitute general, flexible intelligence—robust common sense, long-term planning, causal reasoning, world models, and safe goal alignment—are not solved in an integrated, reproducible way. Demonstrating superhuman performance on a set of benchmarks is not the same as demonstrating general, transferable understanding.

Technical challenges on the path to AGI

- Transfer learning at scale: General intelligence requires systems to transfer knowledge efficiently between disparate tasks without extensive retraining.

- Sample efficiency: Human learners can generalize from few examples; many current models require large labelled datasets.

- Long-term planning and memory: Advanced reasoning requires sustained planning capabilities and memory across extended horizons.

- Robust common sense and causal reasoning: Dealing with real-world variability requires a robust causal understanding of the environment, not just pattern matching.

- Alignment and safety: As capabilities grow, ensuring that systems’ behaviour matches human intent under a wide range of conditions becomes more challenging.

How researchers measure progress

Progress is usually measured through benchmarks and tasks that test specific capabilities: language understanding, reasoning, planning, code synthesis, multimodal tasks (text + image), and generalization tests. However, benchmarks have limitations: they can be gamed, they may not represent real operational complexity, and they may not measure safe or aligned behaviour. Broad, multi-task evaluation suites and reproducible, open evaluations help build confidence, but they are not a single proof of AGI.

Interpretation of recent capabilities

Large language models and multimodal systems now show surprising capabilities across many tasks; they can summarize, translate, generate code, and assist creative work. Those developments indicate rapid progress in certain classes of architectures and scale-related improvements. Yet, being strong at many benchmarks does not imply the presence of generalized understanding or persistent goals—the hallmarks of AGI.

Part 3 — Artificial Superintelligence (ASI): Possibilities, uncertainties, and why careful language matters

What ASI refers to

ASI is a hypothetical future stage where artificial systems exceed human cognitive ability across a broad range of domains—scientific creativity, strategic planning, social cognition, and more. ASI discussions often consider scenarios where systems can improve themselves (recursive self-improvement) or design superior successors, which raises profound technical and governance questions.

Why ASI is speculative

ASI depends on scientific breakthroughs that remain hypothetical today: building integrated cognitive architectures that reliably outperform human reasoning in open-ended tasks, ensuring safety and alignment during self-improvement, and solving thorny problems around value specification. Because these steps are not guaranteed, ASI remains a legitimate subject for long-term research and philosophical discussion, but it is not a near-term operational certainty.

How to treat ASI in policy and planning

While ASI is speculative, prudent long-term planning calls for research into alignment and coordination strategies, because the consequences of very powerful systems could be large. However, policymakers and organisations should balance attention between long-term hypothetical risks and immediate, tractable harms caused by ANI systems (bias, misuse, safety failures). Both timeframes require different governance instruments and research priorities.

Part 4 — Common confusions and how to read headlines about “AGI” and “superintelligence”

Benchmark performance ≠ AGI

A model that achieves state-of-the-art performance on several benchmarks demonstrates impressive capability in narrow contexts. It does not automatically demonstrate general understanding or robust transferability. Reporters and readers should look for independent evaluation, reproducibility, and cross-domain evidence before inferring AGI.

“Emergent” behaviour vs. intended capability

Researchers sometimes report emergent capabilities: abilities that appear at certain model scales or configurations. Emergence is interesting, but emergent behaviour confined to narrow tasks still falls under ANI unless it shows consistent, flexible transfer across unrelated tasks without task-specific fine-tuning.

Be cautious with vendor demos

Marketing demonstrations can be curated and do not reflect real-world robustness. Request reproducible evaluations, test cases, and third-party audits if a vendor claims AGI-level capabilities.

Part 5 — Risks and prioritisation: what matters now

Prioritise near-term, documented harms

Many concrete harms flow from ANI systems and deserve immediate attention:

- Bias and fairness: When models are trained on biased data, they can produce discriminatory outcomes.

- Safety and reliability: Erroneous outputs in high-stakes contexts (healthcare, legal, finance) can cause real damage.

- Abuse and misuse: Tools for generating synthetic media or automating scams can scale harmful activities.

- Concentration of power and economic effects: Large organisations with access to large datasets and compute can gain outsized influence.

Address both technical and governance controls

Mitigations should combine engineering practices with governance measures:

- Technical controls: robust testing, explainability tools, monitoring pipelines, and human-in-the-loop fallbacks.

- Governance: procurement standards, model documentation (model cards), vendor audits, and sectoral regulation for high-risk applications.

Part 6 — Safety, alignment and the research agenda

What “alignment” means in practice

Alignment means ensuring that a system’s behaviour reflects the goals and constraints intended by its designers and users, especially under deployment conditions different from training. For ANI systems, alignment focuses on minimizing bias, making outputs interpretable, and ensuring fail-safe pathways. For more capable, general systems, alignment research studies how to ensure robust, safe objectives that do not produce harmful unintended behaviour.

Research directions that help both near and long term

- Techniques for interpretability and explainability that allow humans to understand model decisions.

- Robustness methods that improve performance under distributional shift and adversarial inputs.

- Human-in-the-loop systems that combine automated assistance with human review for critical decisions.

- Formal verification tools and modular design principles for safety-critical components.

Part 7 — Practical guidance for decision-makers and non-technical readers

A short checklist when evaluating AI projects or claims

- Scope and intent: Is the system solving a well-scoped, measurable problem? Narrow, measurable problems are easier and safer to pilot.

- Data suitability: Does the training data reflect the population and conditions where the system will operate?

- Evaluation and metrics: Are clear, relevant metrics defined and are test datasets realistic and held out from training?

- Transparency: Does the vendor or team provide model documentation, limitations, and known failure modes?

- Audit and monitoring: Is there a plan to track performance metrics and respond to drift or failures?

- Human oversight: Are there escalation pathways and human review for high-risk decisions?

Procurement and vendor questions

Ask vendors for reproducible benchmarks, third-party audits, details on training datasets, privacy and security controls, and documented limitations. Avoid accepting marketing claims at face value—request test cases that reflect your operational environment.

When to involve specialists

Call in ML engineers, data scientists, and ethicists when the system affects safety, compliance, or vulnerable groups. For many low-risk pilots, product managers and analysts can run initial tests with clear oversight and escalation plans.

Part 8 — Examples and short case studies (lessons learned)

Success: targeted automation that reduced manual work

A retail operation used an ANI model to detect low-quality product photos and route suspicious listings for manual review. Because the problem was well scoped, the team could collect 1,000 labeled examples, validate performance, and deploy a monitoring dashboard. The outcome: faster listing quality control and fewer returns.

Failure: biased model in hiring screening

In another case, a hiring screening model trained on historical data learned to prefer candidates from certain universities, reproducing past biases. The organisation had not audited for fairness nor monitored disparate impact. The lesson: build fairness checks into evaluation and maintain human review for consequential decisions.

Misuse example: synthetic media and disinformation

Easy generation of realistic synthetic media has increased the scale of potential abuse. Organisations and platforms need detection tools, transparent provenance metadata, and clear user policies to manage this risk.

Part 9 — Policy and governance recommendations (actionable items)

Short-term (operational) actions

- Adopt model documentation standards (dataset descriptions, intended use, known limitations).

- Require pre-deployment testing under realistic conditions and adversarial scenarios.

- Establish human review for high-impact decisions and maintain logging for auditability.

- Implement data governance for training and input data quality control.

Medium and long-term policy considerations

- Encourage independent third-party testing and reproducible benchmarks for critical systems.

- Support research into alignment and robustness, with funding for open, cross-institutional work.

- Coordinate internationally on standards for transparency, safety, and incident reporting.

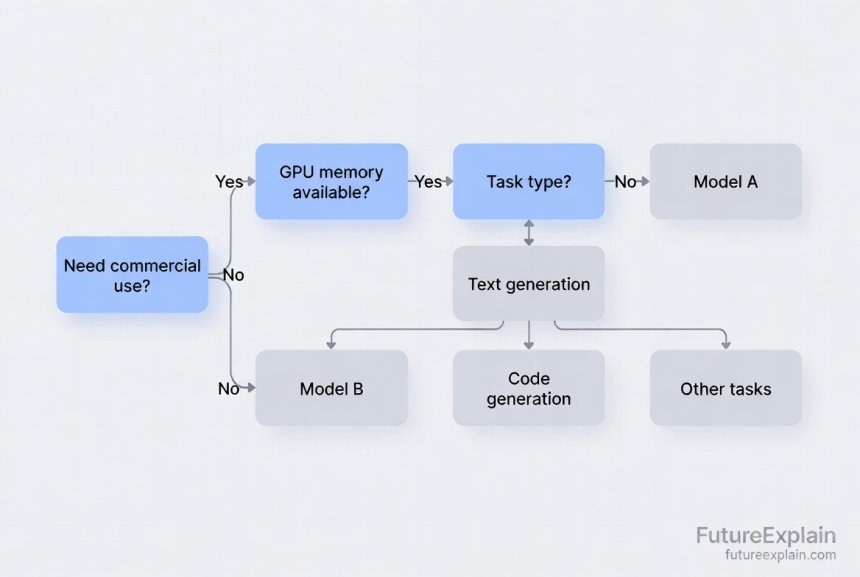

Part 10 — Technical pathways researchers discuss toward AGI and their implications

Researchers pursue diverse approaches toward broader AI capabilities. Some emphasise scale and general architectures (larger models, more compute, multi-modal data). Others emphasise structured, symbolic reasoning, modular systems, explicit world models, or hybrid architectures that combine neural and symbolic methods. Each path has trade-offs: scale approaches benefit from transfer but raise compute and centralisation concerns; modular approaches may aid interpretability but face integration challenges.

From a governance perspective, technical choices influence controllability, explainability, and the kinds of safeguards that are realistic to build into deployed systems. Encouraging research diversity and funding open evaluation helps make progress more transparent and safer.

Part 11 — Ethical considerations and social context

AI technologies interact with social systems. Ethical questions include who benefits from automation, who bears the costs of displacement, how privacy is protected, and how power concentrations are managed. Organizations should apply fairness impact assessments, consult affected communities, and align deployments with social values, not only short-term productivity gains.

Part 12 — How to follow credible developments without noise

To stay informed use a mix of sources: peer-reviewed research, transparent lab reports, reputable technical journalism that provides context, and independent audits. Be sceptical of single-demo claims and prefer reproducible results. Encourage vendors and researchers to publish evaluation datasets, code, and methods where possible so others can reproduce and validate claims.

Part 13 — Practical checklist: evaluating AGI claims in media and vendor announcements

- Is the claim reproducible and independently verified?

- Does the evaluation test cross-domain transfer without task-specific fine-tuning?

- Are safety and failure modes discussed, or is the announcement marketing-focused?

- Are performance gains measured on realistic data representative of operational use?

- Is there transparent documentation of training data, compute, and model limitations?

Part 14 — A concise glossary

- ANI (Artificial Narrow Intelligence): Specialist systems that perform narrow tasks.

- AGI (Artificial General Intelligence): Hypothetical general, human-level intelligence across tasks.

- ASI (Artificial Superintelligence): Hypothetical intelligence beyond human capability.

- Transfer learning: Reusing knowledge learned on one task to accelerate learning on another.

- Model drift: Decline in model performance due to changes in input data distribution.

- Alignment: Ensuring model behaviour matches intended human goals and constraints.

Part 15 — Final recommendations (practical and realistic)

For business leaders and decision-makers:

- Prioritise narrowly scoped, measurable pilots that deliver immediate business value and are auditable.

- Invest in data quality, monitoring, and human oversight before scaling up automation.

- Require transparency from vendors and insist on test cases that reflect your operational reality.

- Balance attention between near-term harms (bias, misuse, safety) and long-term research into alignment and coordination.

For students and general readers:

- Learn core concepts through approachable, hands-on resources; try small, low-risk experiments using pre-trained models and public datasets.

- Read responsibly: prefer reproducible, peer-reviewed results and independent evaluations over sensational headlines.

Further reading

- What Is Artificial Intelligence? A Complete Beginner’s Guide

- AI Myths vs Reality: What AI Can and Cannot Do

- Is Artificial Intelligence Safe? Risks, Ethics, and Responsible Use

This guide is intentionally non-technical and focused on practical decision making. It is not exhaustive: the fields of AI capability, safety research, and governance are active and evolving. For operational work, combine internal expertise with independent technical review and adopt incremental pilots with clear metrics, human oversight, and documented limitations.

If you would like, we can produce a condensed one-page checklist or a slide deck summarising the key takeaways for executives and procurement teams. We can also prepare a follow-up piece that reviews recent research milestones and provides annotated references if you prefer a more research-oriented companion.

Share

What's Your Reaction?

Like

1700

Like

1700

Dislike

30

Dislike

30

Love

320

Love

320

Funny

45

Funny

45

Angry

4

Angry

4

Sad

10

Sad

10

Wow

210

Wow

210

This is the kind of balanced explainer we need more of.

Thanks — the distinctions are clearer now. Useful read.

I'll use this to guide a short internal briefing on AI types.

A good primer to recommend to decision-makers.

Informative and calm — great overview.

Clear and useful. I'll share with my team lead.